Sorry, no records were found. Please adjust your search criteria and try again.

Sorry, unable to load the Maps API.

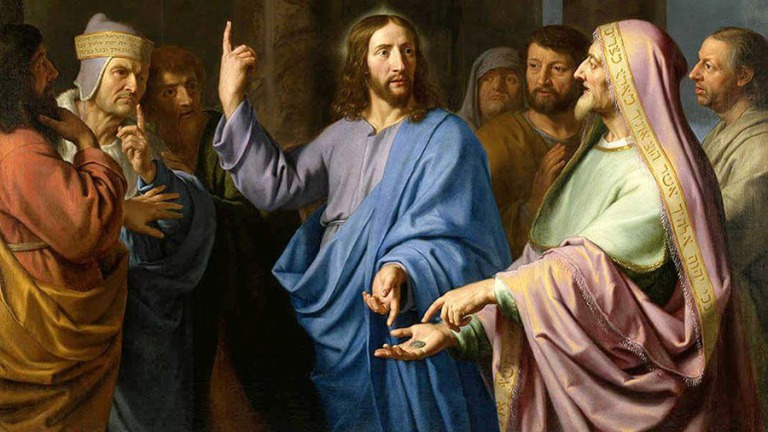

It’s probably one of the most enigmatic and powerful stories in the Bible – the dilemma posed to Jesus on whether or not it was lawful to pay taxes to Caesar (Mt 22:17) has both inspired and confounded Christians ever since Our Lord uttered those iconic words “Render therefore to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s” (v. 21).

This story, and the response of Jesus, has come – rightly or wrongly – to form the foundation stone of many Catholic social justice programmes. Whether it’s the desired-for separation of Christian society and the state, the separation of theology from economics, or simply the justification for radical social action, almost everyone has their own take on this biblical moment of entrapment and intrigue.

As this was last Sunday’s Gospel reading, it was no surprise that Pope Francis took the opportunity to give his interpretation of the encounter, and to address what he saw as ‘incorrect’ or ‘reductive’ uses of the story.

Just to recap – a group of Pharisees and Herodians try to entrap Jesus, as they were often wont to do. “Is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar, or not?” they ask. Tricky, as on the one hand the Caesar’s taxes were resented and legitimising them would put Jesus on the side of an unpopular dictatorship. However, coming down on the side of taxes being unlawful would place him at great risk of accusations of insurrection. Jesus asks to see a coin with Caesar’s head on it and replies: “Render therefore to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.”

Apparently, that was job done as far as Jesus, his protagonists and the scripture writers were concerned, though you’d be forgiven for wondering exactly what was meant by Jesus’ response. And you wouldn’t be the only one – perhaps more than any other passage in the Bible, this particular story has been misused and misinterpreted consistently over time, and it pops up in countless variant contexts across most Catholic social teaching programmes.

Perhaps the most common misunderstanding is that Jesus is telling us that if something has the state stamped on it, it’s the state’s property, but anything that has God stamped on it belongs to God. Oddly, this isn’t actually very helpful in terms of the situation Jesus found himself in – to me at least his answer tips heavily in favour of accepting taxation, which is maybe why the duplicitous Pharisees and Herodians were so easily placated.

For many theologians the latter half of Jesus’ response is the bit that matters – that is, you can say what you like about what the state does or doesn’t own but ultimately it’s the things that God owns that matters. It’s at this point that the analytical narrative has diverged into numerous, often contrary schools of thought, most of them philosophically questionable. For instance, one popular narrative says that Jesus is creating a clear division between corporeal possessions and spiritual wealth – pay your taxes with your state-given salary, but pay homage to God only. This argument has been much favoured by those who see their faith as a counter to the physical world, and is also often used to justify and separate the grubby realities of everyday life, and the aspiration to divine detachment.

Another common variant is that Jesus might be pointing out that whilst coinage might be the legal property of the state, all things in the world have been created by God, therefore even something as mundane as currency should be at the service of God rather than Man.

Like most enduring stories, the best ones tend to be the most adaptable and thus bear the most potential interpretations – and numerous volumes have been built on this particular biblical passage.

Whatever your view of the ‘render unto Caesar’ dilemma, the common thread is the complex relationship between obedience to the state, personal autonomy and devotion to God.

If one tracks back to St Augustine, from whom so many Catholic principles derive, we find an uncomfortable and pessimistic view of the person/state relationship. For Augustine, mankind was created and delivered into an earthy, sentient idyll that required no governance, as there was unquestioning obedience to God. With the Fall, the murder of Abel and all that followed, mankind revealed its flawed nature and therefore subsequently required governance – to contain any further wickedness and to restore some kind of order to the world.

Thus, world leaders become God’s ministers, and there is no right of civil disobedience – even when rulers become despots, but the obligation for believers to follow God’s laws remains. So, when the state’s laws and God’s laws come into conflict, citizens must obey God’s laws – but also willingly accept the punishment of the state for their wrongdoing.

Unfortunaly, the Augustinian view that the state must blindly do what it does, and the citizen must blindly do what it must, is at the root of many of the world’s most horrific tragedies, as we’ve seen so graphically in recent conflicts – for instance in Ukraine and now in Israel and Gaza.

For me, the failure to reconcile the mundane laws of human society with the divine laws of God is one of the greatest tragedies of the human condition and is why we seem endlessly trapped in cycles of dreadful conflict and killing.

I was pleased, therefore, that Pope Francis seems to be of a similar mind on this one.

In his Angelus message he spoke in typically frank terms of a damaging divide between faith and real life that the ‘render unto Caesar’ story has created in the minds of so many Christians:

“These words of Jesus have become commonplace, but at times they have been used incorrectly – or at least reductively – to talk about the relations between Church and State, Christians and politics; often they are interpreted as though Jesus wanted to separate “Caesar” from “God”, that is, earthly from spiritual reality. At times we too think in this way: faith with its practices is one thing, and daily life is another. And this will not do. No. This is a form of “schizophrenia”, as if faith had nothing to do with real life, with the challenges of society, with social justice, with politics and so forth.”

So, when it comes to Caesar’s Coin, Francis clearly belongs to the ‘God trumps everything’ school of interpretation:

“… Jesus affirms the fundamental reality: that man belongs to God: all of man and every human being. And this means that we do not belong to any earthly reality, to any “Caesar”. We are the Lord’s, and we must not be slaves to any earthly power. On the coin, then, there is the image of the emperor, but Jesus reminds us that our lives are imprinted with the image of God, which nothing and no-one can obscure. The things of this world belong to Caesar, but man and the world itself belong to God: do not forget this!”

That may settle who takes precedence in safe harbours, but it’s still left to the Christian citizen to navigate the stormier seas, and to discern for themselves what course to take when the machinations of the state come into conflict with the way to God. Perhaps it’s just a consequence of the continuing deteriorating condition of humanity since the Fall but increasingly we are finding ourselves living in a world where it’s becoming difficult to follow the pathways of God – as invariably the state is there blocking the way.

In one respect Pope Francis is absolutely right to point out that the human person cannot disengage themselves from worldly affairs, but it’s important to emphasise that this doesn’t mean a trade-off, where supposedly necessary material sins can be set apart from spiritual striving a kind of ‘of this world, but not of it’ argument that we often hear promulgated in Catholic circles. It might be more accurate to say that we are ‘of this world, AND part of it’.

In the end we should not separate our Catholic faith from our public witness, and our political choices and actions. As Pope Francis pointed out last Sunday:

Do we remember that we belong to the Lord, or do we let ourselves be shaped by the logic of the world and make work, politics and money our idols to be worshipped?

The answer to this can be found elsewhere in the bible, in the arrest of the apostles by the Sanhedrin (Acts 5:28-29). When the high priest chastises the apostles for promulgating Jesus’ teachings and the unrest that his words were creating, Peter simply says: “We must obey God rather than men.”

This may not be the easiest or most obvious route to conflict resolution, as the divine mandate is debatable – and in the modern world it’s at the seat of much that divides humanity. But it’s what the Catechism tells us to do:

Christians should be subject to those in authority, but they have “the right, and at times the duty, to voice their just criticisms” for the good of the community (CCC 2238). They also need to lead an active political life (CCC 2239-40). When civil authorities issue immoral commands, Christians are to refuse to obey them (CCC 2242).

In extreme cases the Catechism even endorses progressively greater resistance and, if all else fails, even armed resistance (CCC2243).

This may sound extreme, but it’s clear evidence of how far humanity has declined from the time when matters of state and matters of theology were pretty much complimentary. In fact, it’s rather anachronistic to divide the world into what belongs to Caesar, and what belongs to God, as they really ought to be one and the same. This is especially true in the case of modern-day nation states, where the separation of the temporal and spiritual has become almost complete. In this respect it’s actually quite difficult to analyse contemporary social dilemmas in the context of the biblical episode of Caesar’s coin.

A more robust response might be to approach all such worldy problems and contemporary challenges on the premis of Psalm 24, which begins, “The earth is the LORD’s and all that is in it, the world, and those who live in it.”

If we forget this, the Church is in severe danger of disappearing as a social body, and along with that goes the hope that Christ’s redemptive power can transform and heal the ills of the world.

Joseph Kelly is a Catholic publisher and theologian