Sorry, no records were found. Please adjust your search criteria and try again.

Sorry, unable to load the Maps API.

One the great benefits of decades in Catholic journalism is that you not only acquire unique memories, but a miscellany of artefacts charting your journey. Having grown up in a world before the internet I developed an early fascination with books, and with English Catholic history, so my particular 30 years in Catholic journalism is landmarked by the titles that line my bookshelves. For me, to leaf through a text from centuries past is to share a journey with all those far greater than me who may have held the book before.

The oldest book in my collection is a fabulously aged but readily readable 1697 English edition of Fr Aphonsus Rodriguez SJ’s The Practice of Christian Perfection. Born in Valladolid, Spain in 1538, Alonso (as he was more commonly known) was a remarkable ascetic who joined the Jesuits aged 20 and went on teach moral theology in Cordova and the College of Monterey, where he was rector for 17 years. Rather remarkably for someone with such qualifications Alonso only wrote the one book, though it has been reprinted constantly over the centuries, with at least 100 extant editions in numerous languages.

Written in very accessible language, it avoids the complexities of theology but rather is a practical guide to the qualities required to lead a good Christian life, and the book remained in popular use for those contemplating a religious vocation right up to the time of the Second Vatican Council.

In many respects Alonso’s book is typical of many of the Catholic texts that were published during the Counter-Reformation period, and I hear in it close echoes of another book that has obsessed me during my years in Catholic journalism – the Welsh Catholic book Y Drych Cristianogawl (The Christian Mirror) dating from 1586 and generally believed to be the first book of any type actually known to have been printed on Welsh soil. My Welsh is rudimentary, and my knowledge of old Welsh even more so, but even I can catch glimpses in the text of the writer’s impassioned plea for Catholics not to desert their faith in times of difficulty, but to hold fast to the principles of a good Christian life, even when everything and everyone in society seems to be running against you.

Although both the author of Y Drych and Fr Alonso were writing nearly 500 years ago, so much of what they say is sharply apposite to the present day-state of Catholicism, and Christian practice in general. As those who’ve been involved in recent and ongoing meeting about synodality and the future of our Church will know only too well, one of the greatest challenges we face today is how to respond to the pressures of the aggressive secularism that surrounds us, and at the same time preserve our right to the practice of our Catholic faith.

For the Catholic writers of the Counter-Reformation period the dangers of advocating the practice of the faith were acutely real and life-threatening. Throughout most of the Catholic writings of the period its hard to avoid a sub-script of urgency, but never is there any sense of desperation or hopelessness, rather a conviction that Catholics need only to be reminded of what they have, and want went before, to hold fast to their faith.

It is interesting to me that Alonso’s mighty three volume work, which had become a staple read for those seeking a religious life, fell into sharp disuse after the Second Vatican Council. As the Catholic Church ‘opened its doors and windows to the world’, so many things were discarded in the search for a Christian narrative with a contemporary relevance. Sadly, this wasn’t done too well, and in many ways only served to clarify a pre-existing theological divide between those who wish to look backwards and cling to tradition, and those who wanted the Church to abandon all that and engage with modernity. 60 years on we’re still a long way short of reconciling the need to preserve our traditions against the need to respond to a society that is becoming increasingly intolerant towards the practice of any faith.

As a Catholic journalist you observe the constant stream of news and information relating to the Faith that passes cross your computer screen, and you become aware of trends, tendencies and connections between often otherwise unrelated events. In recent weeks there has been a regular stream of reports of random arson attacks on Catholic churches across Europe and the USA, often accompanied by messages of a general anti-Catholic nature, rather than any specific grievance. Conversely we are seeing an increase in overtly Catholic demonstrations and public gestures – from city centre rosary prayers to civic demonstrations. Sadly, the overall impression is not one of reconciliation or tolerance, but of increasing division and belligerence on both sides of the faith debate which is less than helpful to Catholics who just want to practice their faith and live as Christian a life as possible.

In the face of such turbulence it’s all too easy to become despondent, and to think in terms of our faith diminishing, which is one the main reasons why Pope Francis has activated the synodal process.

“There is no need to create another Church, but to create a different Church,” Francis said ahead of the solemn inauguration of the Synod, citing Dominican priest Father Yves Marie-Joseph Congar.

In his 2020 encyclical Fratelli tutti, he also stressed the need for a culture of encounter and dialogue in addressing the major issues of our world, which he said was essential for the internal life of the Church.

For many this concept of a ‘different’ Church that is somehow not ‘another’ Church is difficult to reconcile, but what is bring sought is a Church that doesn’t abandon its history and first principles, but rather changes the way it presents itself to the world, especially in response to the many challenges of our time.

In this I’m reminded very much of a very moving and candid letter that Cardinal Newman wrote to the attendees of a Catholic Truth Society Conference held in Birmingham in 1890. In it he said: “I may say of myself that time has been when I have had much sorrow to see that the prospects of the Church have shown in England so little hopes of brightening. There has been – there is now – a great opposition against the Church. But this day and this hour are the dayspring of its revelation. I have had despondency; perhaps at times I have done wrong to despond too deeply; but the hour has come when … we may put to good use and practical advantage the privilege which God has given us. May he sustain you, for He is not wanting if you are ready to the work. And for myself and for you, I hope that you will bury and forget my weakness in your strength. God Bless you.”

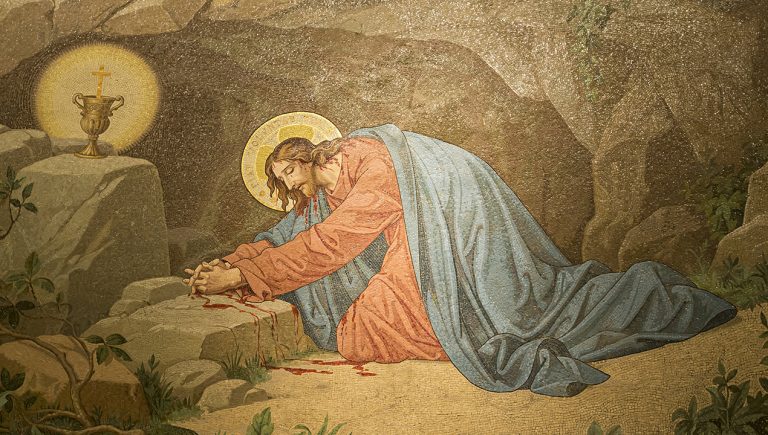

It has ever been a characteristic of our Catholic Church that moments of the greatest despair are oftimes also the moments of the greatest hope, when we ought to have less fear and more confidence in God’s wisdom – the lesson from Gethsemane.

The present turbulence and uncertainties we Catholics are facing may seem like the first beginnings of the last end, but whenever doubt sets in, let’s remind ourselves of the words of Our Blessed Lord and the need to have faith in the purpose that God has set out for us: ‘if you are willing, take this cup away from me. Nevertheless, let your will be done, not mine.’ (Luke 22:42)

Joseph Kelly is a Catholic publisher and theologian